My name is Jane. I am a photographer from Ukraine. The war caught up with me when I was in my village, Cherkas’kiy Tyshky, with my grandfather and grandmother. We were occupied instantly on February 24, 2022, at 6 a.m.

15 kilometers is the distance that separated our village, which is under occupation by Russian forces, and Kharkiv, which is held by Ukrainian troops.

My village, which is between Kharkiv and the Russian border, is still under occupation. I managed to escape, but I spent twenty days there, which I will describe in this weekly column.

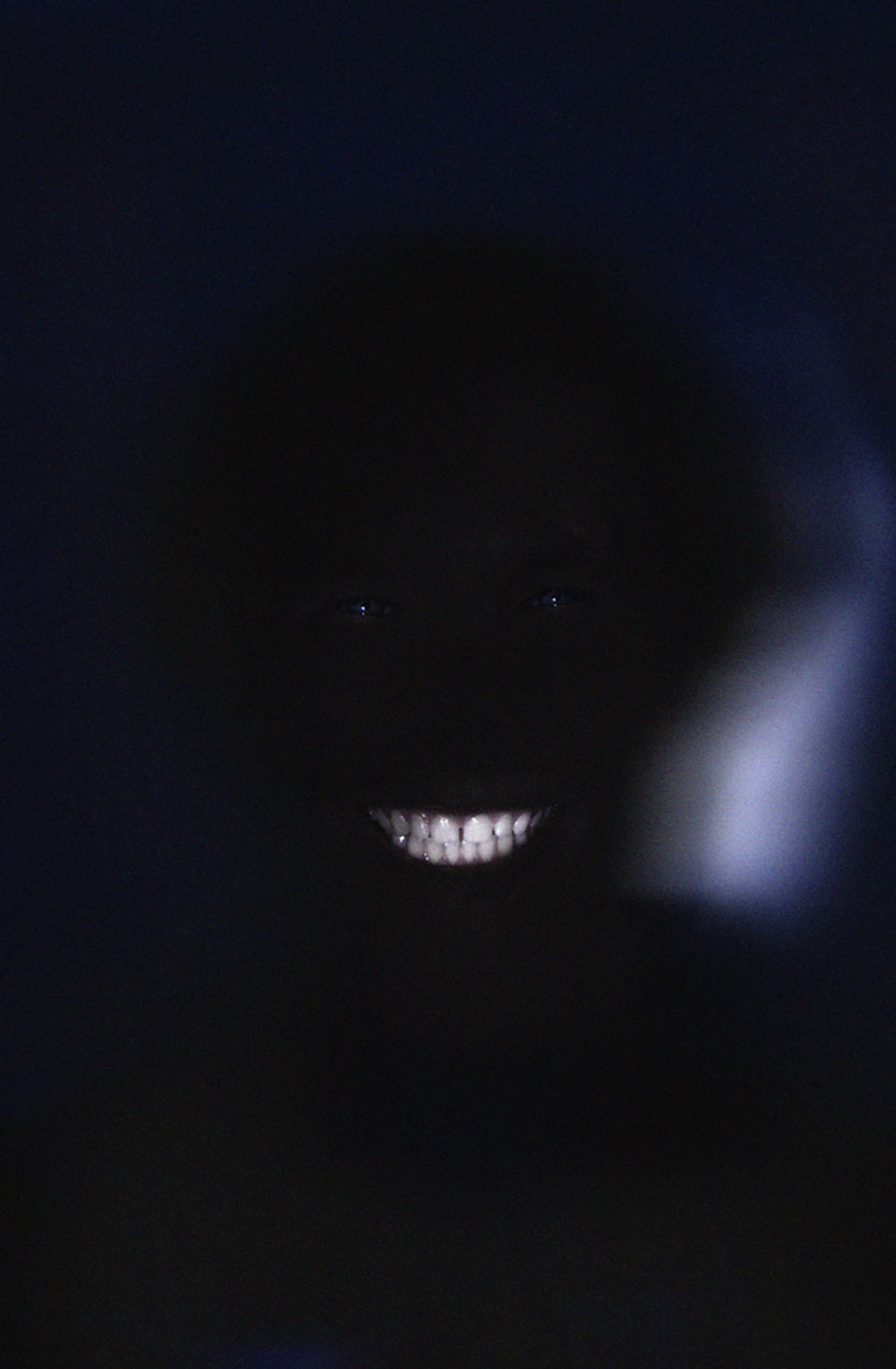

Death

Death comes from the right side. She stands next to you.

“Come with me. It’s time to go,” she says.

And you lay in a cellar as in an ancient sarcophagus, and you cannot move. Only your voice rings in your head, entreating for mercy.

“Please, do not take me. Let me live a little bit longer”.

Death leaves…for some time.

Death comes from the right side, she stands behind you, and whispers in your ear.

“Come with me. It’s time to go”.

“Please, take mercy on me. I do not promise anything, and I do not worship anyone. I am no one, I am no better or worse than the others. I just want to live—it is the only thing I have left, the only thing I know. Life,” you answer her.

Death comes to you, purring. She climbs on the sarcophagus, in which you are buried alive. She tramples on your throat with her fluffy paws. She chokes you with her delicate love.

“Come with me. Your time has come,” she says.

“Please, let me survive this sacred war. It’s too soon for me to leave. I want to live,” you answer.

Death does not have a face. She is ashamed of it. She is afraid to look people in the eyes. She comes quietly, sneaks in, and injects poison.

“Come with me. Your time has come,” she whispers.

Your body weakens, it dives into the dream of inexistence.

Death does not have a face, she only has a back. The old woman with short hair looks at you with the back of her head.

“Come with me. Your time has come,” she whispers gently, lulling you to sleep.

* * *

Meat

War is all about meat. There were two types of it sent to us: human and animal. There was so much of it that you could suffocate from its stench. It would rot in front of you; it would rot inside you. You were only a piece of meat, too.

There is no time in the war. There is only endless waiting, and the only thing you can fill it with is food. Though, you run out of it quickly. The first thing you eat up is bread, then vegetables and fruits, until you are left only with meat. But the meat is eaten up eventually, and then you go to get humanitarian aid. There, they give you more meat, which they have brought from the bombed farms. They bring carcasses in their big trucks and unload them on the ground.

Meat lays there in big piles, rotting and bleeding, while people, like hyenas, grab a bigger piece and drag it home.

There has been no electricity since the beginning of the war. Thus, people salt the meat, boil it and can it. The young meat with the letter Z rots in the fields. We had meat for breakfast, lunch and dinner. As if we were eating those dead, rotten soldiers.

Sometimes it seems to me that meat circulates my veins instead of blood, that my lungs have no air in them, only meat.

They brought a lot of young meat to us—18 years old. Sometimes I would look it in the eyes and think, “You are so beautiful. Why do you need this war? It would be better to sit in jail for seven years and stay alive. But now you are meat. Just meat.”

Though, me too.