FLUXUS IN GERMANY 1962-1994

“A Long Tale with Many Knots”: Bucharest celebrates the Fluxus artists with a large exhibition dedicated to their activities in Germany.

Text by Anna Battista

Considered by some critics as a radical artistic movement, Fluxus was actually a collective of artists, writers and musicians with a passion for experimentation and performance and a playful, irreverent and cheeky approach to life.

Originated in the ‘60s, the scene found fertile ground in the German cities of Darmstadt, Duesseldorf, Cologne, Wuppertal, Wiesbaden and Berlin and the country ended up playing a crucial role in the growth of Fluxus.

The connection between Fluxus and Germany is analysed in an exhibition currently on at Bucharest’s Muzeul Naţional de Artă Contemporană (Museum of Contemporary Art – MNAC).

Curated by René Block and organised by the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen Stuttgart with the support of the German Embassy in Bucharest and the Goethe Institute, “Fluxus in Germany 1962-1994: A Long Tale with Many Knots” occupies the two main galleries on the ground floor of the museum and the ground floor balcony.

Devised in 1961 by Lithuanian artist George Maciunas as the title for an “International Magazine of the Newest Art, Anti-Art, Anti-Music, Poetry, Anti-Poetry, etc”, Fluxus was inspired by different influences, from Futurist performances and silent films to Dada.

The word “fluxus”, a term that comes from the Latin root meaning “to flow”, was supposed to call to mind a fluid bowel discharge and had as main purpose, in Maciunas’ words, that of purging “the world of bourgeois sickness, ‘intellectual’, professional and commercialised culture, dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic art”, while promoting “a revolutionary flood and tide in art, (…) living art, anti-art, non-art reality to be grasped by all people, not only critics, dilettantes and professionals”.

As various collaborators – George Brecht, Ben Vautier, Nam June Paik, Dick Higgins and Joseph Beuys – joined Maciunas, the Fluxus group started inspiring artists all over the world, prompting them to experiment in different media, from visual art to performance, music and poetry happenings.

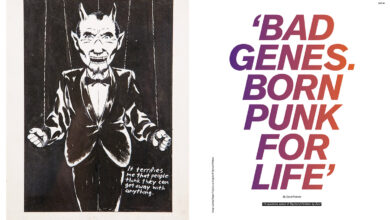

In its role of international anti-art collective that challenged the distinctions between artistic genres and works and the notions of authorship and ownership, Fluxus tried to democratise art and spark up a cultural revolution.

Some of the materials exhibited in the main gallery of the museum, including posters, letters, graphic design and typography projects, objects, collages, illustrations and drawings, books, prints, music scores, kits and boxes – such as Gerhard Rühm’s “Attempt of a Reconstruction”, Robert Rehfeldt’s “Ohne Titel”, Daniel Spoerri’s “Napoleon” box and George Brecht’s iconic “Water Yam” with typeset by Tomas Schmit – perfectly show how these pieces were supposed to transcend the main categories of art, mixing them all together.

One of the most famous pieces on display on this floor is Maciunas’s “Excreta Fluxorum” box, containing symbolical animal excrements that hint at Fluxus’ “purged” and not crafted art.

In 1962 the Fluxus Festival was held at the Städtisches Museum in Wiesbaden. The event comprised a series of concerts under the title “Fluxus + International Festival of Newest Music” and featured various artists appearing in action music pieces and happenings involving “concrete music”.

Music is naturally one of the strongest parts of this exhibition that features larger installations like Wolf Vostell’s “Fluxus-Piano-Lituania, Hommage à Maciunas”, a composite piece formed by a piano, supermarket trolleys and suitcases, and Milan Knizak’s “Destroyed Music”, broken or melted records framed as if they were paintings.

Rare videos such as Joe Jones’ “Fluxus-Home-Movies” and Manfred Leve’s photographs of musical happenings documenting experimental Fluxus concerts featuring Joseph Beuys and Nam June Paik complete this section.

The second gallery on the ground floor focuses mainly on three artists. Here visitors will be able to listen to more audio recordings and admire Nam June Paik’s “I believe in reincarnation”, a cross formed by television screens beaming assorted images in bright colours and his “Mini-Robot” sculpture, an assemblage of different objects including a camera, a record player and various records.

Joseph Beuys’s “Ja, ja, nee, nee” (Yes, yes, no, no, 1969), a 32 minute audiotape recording in a felt box and his “Bruno Cora-Tea” (1975), a Coca-Cola bottle containing herb tea, with lead seal and label in glass-fronted wooden box, and Henning Christiansen’s “Green Violin” and “Hammer Music”, used at Fluxus concerts and sometimes employed to play with Beuys during the group’s happenings, are also included in this section.

The music thread continues upstairs on the gallery balcony with John Cage’s “Mozart Music” box, and Joe Jones’s musical instruments – wind chimes, a mandoline, a xylophon and two zithers that can be activated by the visitors using five little switches.

The works on display on the balcony perfectly show how the Fluxus artists mainly used mixed media to express themselves: Ben Patterson’s “A Short History of Twentieth Century Art”, is a collage of toys, cheap objects and colourful plastic letters forming messages about the Fluxus collective, while Geoffrey Hendricks’ dreamy “Suitcase of the Clouds” is a simple trunk-shaped case with a cloud-printed lining.

Irony and surrealism are tackled instead in Takako Saito’s Fluxchesses, that is chess sets with liquor bottles, spices, mice traps or tiny models of eyes, and Dieter Roth’s pieces “Droppings Bunny” and “Duck Hunting”, with its knights and duck figures in a landscape of chocolate mould enclosed in a wooden box.

“Art is everywhere; it’s only seeing which stops now and then”, John Cage once claimed: this statement will definitely come to mind to the visitors walking around the galleries at the MNAC, making them realise that the iconoclastic spirit of Fluxus may have spread to other countries, reaching out to the rest of the world, but its goal – eliminating that fastidious boundary between art and life – still remains the same.

“Fluxus in Germany from 1962-1994, A Long Story with Many Knots” is at the Muzeul Naţional de Artă Contemporană, Bucharest, Romania, until 31st January 2012.

Anna Battista’s research trip to Romania was made possible through a journalistic grant from the Institutul Cultural Român (ICR – Romanian Cultural Institute), Bucharest.